Leafa Wilson • 6 September 2018

Curator Leafa Wilson shares her pick of the female finalists from this year's National Contemporary Art Award, on show now until 28 October at the Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato.

I always look forward to the big surprise of the winner at the opening of the National Contemporary Art Award. This year’s winner was Sarah Ziessen’s You and Me and the Weight of History.

Each year, I am the in-house curator assigned to assist with the Award exhibition at Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato. Out of 32 finalists selected by this year’s judge Reuben Friend, Director of Pātaka Art + Museum, I have chosen three works by women that I found intriguing to share.

Lesbians Are Not Women

By Louise Lever

As a hetero cis woman who has had a #2 – 3 cropped hairdo since 1990 coupled with being indelicate, I can relate to Louise Lever’s portrait of Ardy Tibby (a US-born Melburnian who is a respected elder in the Australian lesbian community) which points to the personhood becoming less visible due to people’s insistence on determining what gender she is, based upon her appearance.

This work was made with the vital lesbian text by Monique Wittig ‘One is not born a woman’ (1980) in mind. Lever’s image and Wittig’s text privilege queer language that in turn frees the physical body from the association and literary relationship of the word ‘woman’.

This is a utopic space. Lever’s work picks up on this notion by the sole subject, Ardy Tibby’s lesbian gaze at the viewer. She and Tibby are interested in the lesbian body as contestably sovereign lesbian ground.

Louise Lever -“Recently, when I was with my girlfriend at a mall we got yelled at ('lesbos!') and then at a cafe a family actually said, 'there’s lesbians in here'. Never have I been accused of being a lesbian out on my own.”

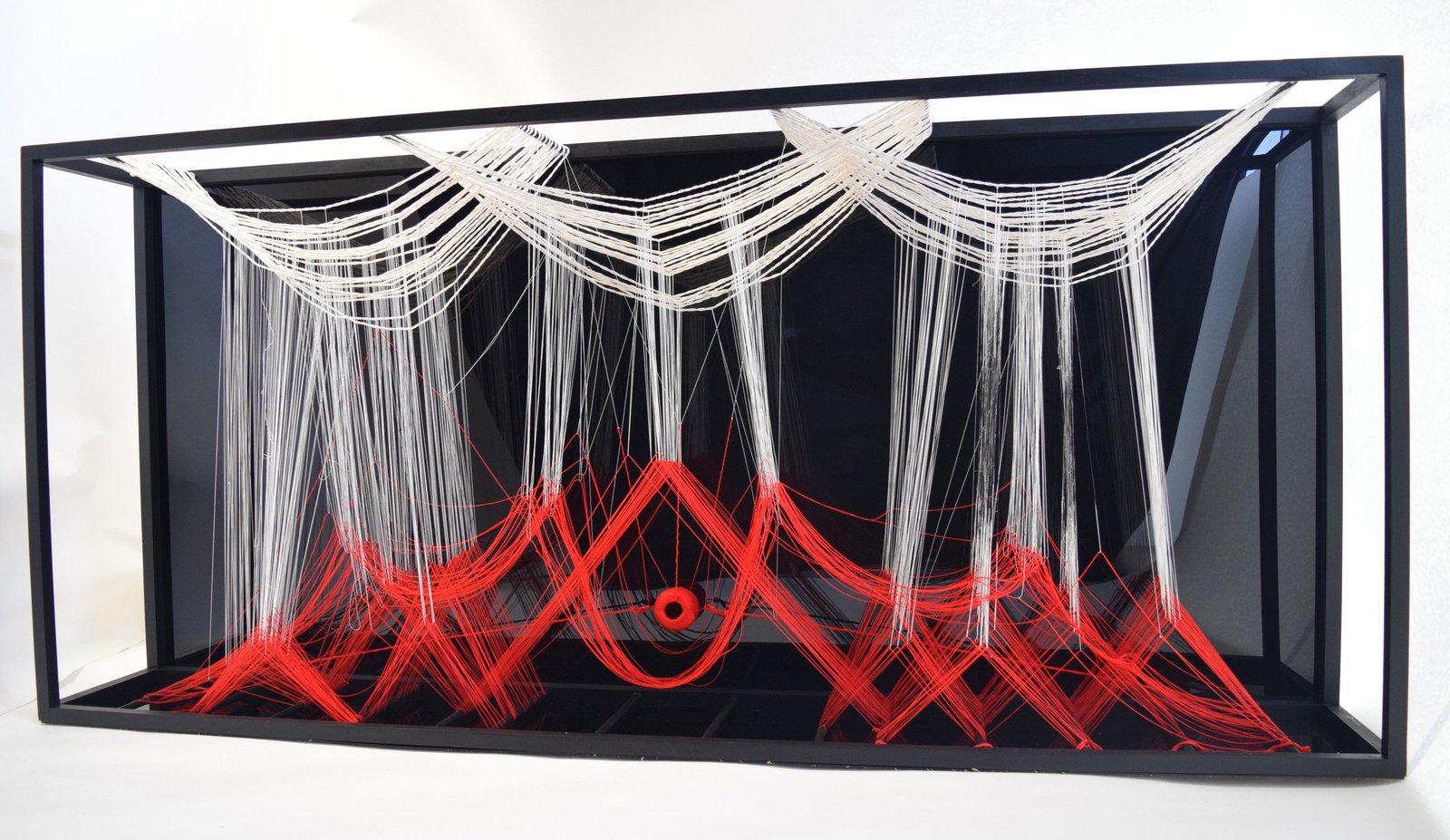

2. Aho Mutungakore

By Tessa Ma'auga

The poetic work of Tessa Ma’auga is deeply entwined with both Chinese and Māori philosophies.

The aho is the sacred first line a weaver makes to begin a weaving in Te Ao Maaori tradition. Visually striking red and white threads against a black ground are intimately bound up in a series of loose whatu (weave) and whenu (warp) which signify the metaphysical concepts of time having no beginning or end. All things that are seen and that which is beyond our sight belong to the life cycle and join the evolution and regeneration of all created things.

The red (red ochre), the white and the black rightly are widely accepted as a traditional and sacred Maaori colour palette: Ma’auga who is the child of American Chinese parents was first educated in Aotearoa at a kura kaupapa bilingual unit that immersed her in Te Ao Maaori and she recently graduated from Massey University’s Bachelor of Maaori Art Degree. Her colour palette sensitively references both her own heritage and pays respects to Tangata Whenua. Ma’auga infuses the ‘red thread of fate’ in Chinese cosmology as her connector to her presence in Aotearoa and to the life Source. This metaphysical red thread is an unbreakable link to those one is destined to meet. Ma’auga’s work is not weaving but uses the methods of weaving in a performative manner to play out the metaphor of interconnectedness through the weaving of time — a thread without end.

“And now collectively we design a fate

With patterns found in a sacred heritage

Trajectories of descent and ascent

Towards a loftier summit.”

Tessa Ma'auga

3. All that Glitters Ain't Gold

By Monique Lacey

The cautionary phrase ‘all that glitters is not gold’ is one of the very first quotations I ever remembered when I was little because it was written in my mother’s adolescent hand-writing on the fly leaf of her daily missal (a Catholic handbook containing all the mass readings and settings for one liturgical cycle). The phrase was made widely known by William Shakespeare (Merchant of Venice, 1605) but has been in use proverbially for centuries prior. It alludes the idea of something not being all that it’s cracked up to be.

This work by Monique Lacey intrigued me for that reason and for the fact that it is a playful work that is not based around identity, emotion or place but materiality and the effect of perception. It is a painting and a sculpture. Lacey has tested the cardboard by body-slamming it into its current shape. Taking away from its former square and perfect self-controlled form. It gives the final painted object a rock-like appearance. The contrasting lightweight flimsy nature of corrugated cardboard box to its exterior that’s covered in gold paint manipulates the viewer to imagine it as a heavy solid, gold object.

The viewer is really part of this work because the anti-climax, as suggested by Lacey’s title, is fully realised when they read her text and see that it’s merely an impression of her body on the wall-mounted ‘gold’ lump. Minimalism has tended to be the austere aesthetic of choice for the spaces where life/world changing decisions are made by men in power. This work subverts the edges of hard-edged minimalism, denying it the chance to be utilised in male-centric power structures.

Monique Lacey -“The work’s crushed Baroqueness and mangled state can appear comical and bodily and perhaps feminine. The works function as benign violations of the established legacies of power that can be tracked through the histories of the Baroque, De Stijl, and Modernism to the power of the boardrooms that became the resting place of Minimalism.”

Leafa Wilson is a curator at the Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato.