Rachel Barrowman • 1 November 2018

In this extract from Creative Victoria, author Rachel Barrowman retraces the creative beginnings and early collaborations of some of Victoria University of Wellington's most well-known students — including Taika Waititi and Bret McKenzie.

Image: Flickr Creative Commons

Image: Flickr Creative Commons

Creative Victoria: A History of 119 Years of Creativity at Victoria University of Wellington by Rachel Barrowman (Victoria University Press, $40.00)

Back up at the university, Drama Studies had gained its independence and become a fully fledged Department of Theatre and Film in 1991, with a major introduced, and a new course in New Zealand theatre and film (partly funded by the New Zealand Film Commission).

The 1990s saw another exceptionally talented cohort pass through the department’s doors and shake up the theatre scene. Jo Randerson switched to theatre after a confused first year of study intending to major in Latin, and graduated in 1994. Alongside her coursework she was prodigiously busy as a director, writer and performer with the Drama Club, performing at BATS and doing television stand-up. Her first play, Fold, performed as part of BATS’ Young and Hungry season in 1995, immediately established her as a distinctive, fresh dramatic voice, with a wickedly funny surrealist imagination. The same year, with Andrew Foster and actors Jo Smith and Jason Whyte, she founded the appositely named theatre group Trouble. Over the next few years they put on a serious of boldly original, provocative shows, beginning in May 1996 with The Girl Who Died (Randerson herself), an extremely bloody black comedy described by critic Mark Amery as ‘slick, innovative, pacey, at times sickening, and completely beyond logic’ and ‘FANTASTIC’. They followed this the same year with a site-specific work, Mouth (performed in Tasman Street), and, back at BATS, Black Monk, based on the Chekov story. The more ambitious, larger-scale The Lead Wait in 1997, commissioned by BATS, was about—in Randerson’s description—‘the lost generation who grew up in the Rogernomics user-pays system, alone and attempting to raise ourselves’, the characters in the play living inside the skeletal structure of a stripped-down house undergoing renovation. The Lead Wait became a cult hit for its unsettling hypernaturalism and dark wit, and was still seen as ‘bold and exciting’, ‘challenging and provocative’ [New Zealand Listener] fourteen years later. There was also a four-year collaboration with Scottish theatre group the Boilerhouse on Bleach, which had performances at the Wellington Fringe and Edinburgh festivals and in Glasgow.

Jo Randerson in Good Night — The End, Barbarian Productions, Downstage, 2009

Jo Randerson in Good Night — The End, Barbarian Productions, Downstage, 2009

Randerson’s writing has not only been for the stage. In 1996 she took Bill Manhire’s Original Composition course (winning the prize for best portfolio), and she has had two collections of short stories published by Victoria University Press: The Spit Children (2000) and The Keys to Hell, with illustrations by Taika Waititi (2004). Her theatre practice, meanwhile, began moving in a different direction when, with Thomas LaHood, she formed Barbarian Productions in 2001—the name deriving from a recent visit to Denmark and finding her family’s Viking roots. Their first show, a ‘weirdly fascinating look at love and redemption through the eyes of a Bach-playing punk’ [Dominion], performed solo by Randerson, was titled Banging Cymbal, Clanging Gong. At first they performed comedy and sketch shows, and toured nationally and overseas—to Australia, Edinburgh, Norway and Prague. Along the way, Randerson trained in clown and commedia dell’arte with Circus Ronaldo in Belgium (while LaHood attended a clown school in Ischia) in 2005. Back at home they began staging larger, more ambitious and authorially driven shows, beginning with Good Night—The End at Downstage in 2009 (‘a 106-minute play about death’ [Dominion]).

Increasingly Barbarian’s practice has emphasised community, collaboration and engagement, and the social function of theatre: ‘We’ve had crazy shows with 60 people . . . gone outside of the venues . . . trying to create a sense of togetherness and the radical, fun energy. It’s about changing the framing of theatre.’ For Randerson, completing a Master of Theatre Arts in Directing in 2012—a two-year degree taught jointly by Victoria and Toi Whakaari, introduced in 2001—was the key spur towards greater experimentation with venue and form.

While Randerson’s career has remained purposefully, and politically, rooted in the local and community, those of her close contemporaries in Theatre and Film at Victoria, Taika Waititi, Bret McKenzie and Jemaine Clement, while not losing their essential hometown connection, have expanded onto a much larger stage—that of the Oscars and Grammys, the BBC and HBO. In the mid- 90s, though, they were all at Victoria doing BAs (only Waititi would graduate) and developing their particular brands of comedy. Along with Carey Smith and David Lawrence (who a few years later would form the Bacchanals), they created So You’re a Man, performing a 1950s-style mockumentary guide to coping with manhood that premiered at the Basement in Auckland in May 1996, had a sell-out season at BATS in October–November and went to Melbourne the following year. Waititi and Clement then became comedy duo the Humourbeasts, and won the Billy T Award—awarded by the New Zealand International Comedy Festival since 1997 and honouring comedy legend Billy T James—in 1999.

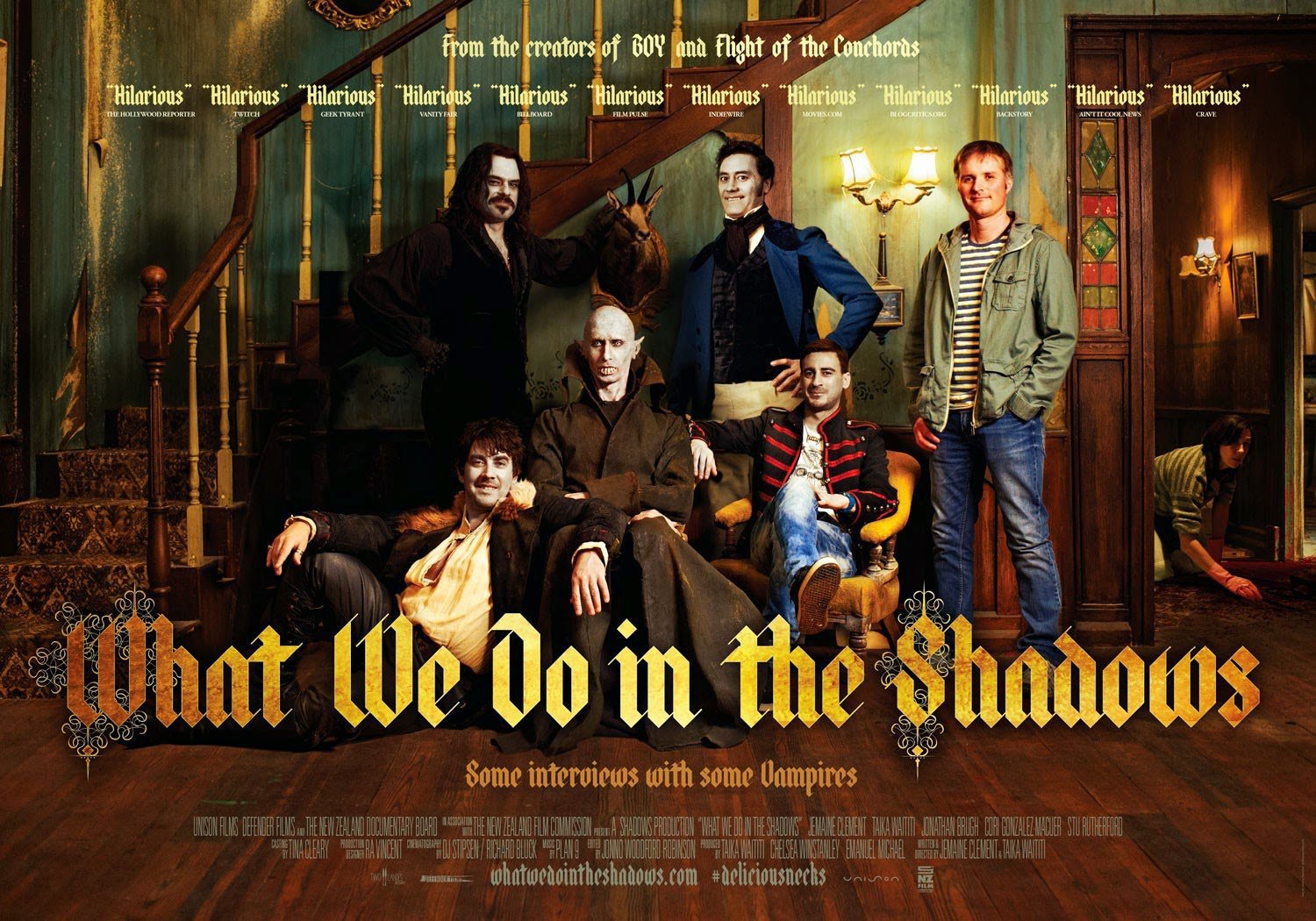

Waititi has also channelled his creative energy into painting, photography and design, but his major work has been as a film director. His first film, Two Cars, One Night (2004), a sweet-funny, understated slice of life, shot in black and white, featuring three children waiting in a pub car park while their parents drink inside, won an Academy Award nomination for Best Live Action Short Film, along with a string of awards both in New Zealand and overseas. It was made during the year or so that Waititi, Randerson and others had the lease of an empty warehouse next to Te Papa: ‘a really formative, magic time’, in Randerson’s recall, with the shared space generating a concentrated creative energy. Waititi followed Two Cars with Tama Tū (2005), a weightier film about the World War Two Māori Battalion, which again was widely screened on the international film festival circuit. He delved into a different, and what would become a signature, comedic vein, though, with his first feature, Eagle vs Shark (2007), a goofy, geeky romantic comedy starring Jemaine Clement and Loren Horsley. This was also the tone of 2014’s urban Wellington vampire spoof What We Do in the Shadows (with Waititi and Clement in the lead vampire roles); to a lesser extent the more affecting coming-of-age Boy (2010), set in his own East Coast hometown, and Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016), based on the Barry Crump novel Wild Pork and Watercress. Wilderpeople quickly became New Zealand’s most successful comedy at the box office since Boy.

While these were well-received too overseas, on the international stage they were small, quirky films from an unfamiliar culture. Waititi moved up to another film-making level (in audience terms at least) as the director of Thor: Ragnarok (2017), the third of Marvel’s Thor franchise based on the comic-book superhero, and refreshingly distinguished from its predecessors by its deadpan, self-deprecating humour and bright-hued, playful 1980s sci-fi aesthetic.

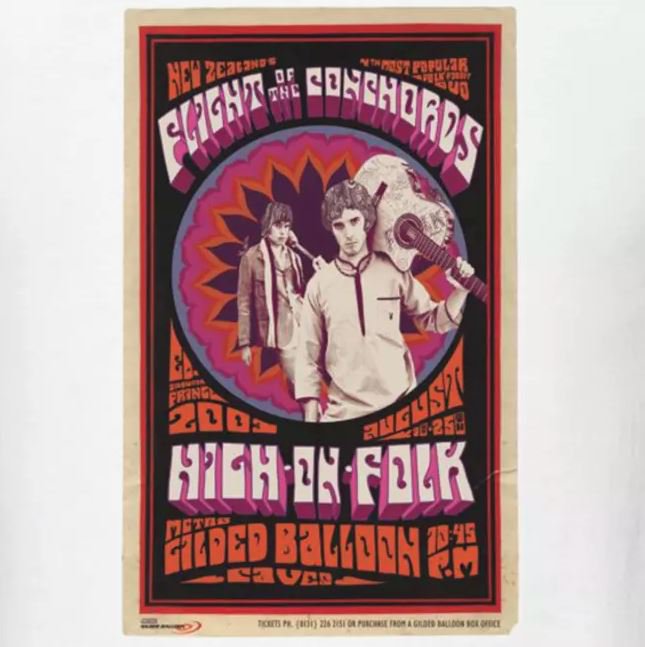

Back to the 1990s, when, in 1998, Bret McKenzie and Jemaine Clement, still at Victoria and flatting together across town in Mt Vic, formed musical comedy duo Flight of the Conchords and took their own, same-but-different style of offbeat comedy to the world. Their first international appearance was at the Calgary Fringe Festival in 2001. The following year they took their show Folk the World from BATS to a turn at the Edinburgh Fringe, where their kookiness combined with their musical craftsmanship made them one of the festival’s breakout, and award-winning, shows: ‘Their shtick was artless banter spliced with improbable comic songs, notable for their pernickety lyrics and eclectic musicianship’ [Guardian]. McKenzie in particular was a highly talented multi-instrumentalist (and classically trained dancer), and he was a founding member of Wellington dub/funk band the Black Seeds. Their 2003 follow-up at Edinburgh, High on Folk, was nominated for a Perrier Award.

In 2005 a six-episode, eponymously titled Flight of the Conchords show (also featuring Rob Brydon and Jimmy Carr) aired on BBC Radio 2. The real breakthrough, though—after a pitch to New Zealand television was turned down—was landing an HBO pilot series in 2007. Here they played themselves as hapless newcomers to New York, failing to make it as a band, with a manager who ‘moonlights as a cultural attaché at the New Zealand consulate’, and feigning to mock—while in so doing, celebrating—New Zealand’s ‘eccentricity and boringness’. There would be a second HBO series in 2009; before that a Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album (2008). If never more than a cult success in the big picture, perhaps, as the Guardian has observed, the Conchords achieved the rare feat of making musical comedy cool, and ‘flew the flag for’ a more arty and intimate, less obvious and aggressive style of comedy. The ‘radical flatness’ of McKenzie’s and Clement’s performances combined with a sense of the surreal was a manner entirely familiar to New Zealand audiences; not so elsewhere.

Parallel with the Conchords’ stellar path, Clement and McKenzie have also pursued busy separate careers: Clement mainly as an actor; McKenzie also as a musician—making a solo album (Prototype, 2004), and winning an Academy Award for Best Original Song for ‘Man or Muppet’, written for the 2011 Disney film The Muppets.

Rachel Barrowman is a biographer and historian. Her books include Mason: The Life of R.A.K. Mason, which won the 2004 Montana New Zealand Book Award for Biography and Memoir, and Maurice Gee: Life and Work, which was a finalist in the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2016.