Marco Sonzogni • 12 November 2017

As Kazuo Ishiguro becomes the latest recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Marco Sonzogni reflects on the world's most esteemed literary prize, and uncovers an unexpected New Zealand connection along the way.

Dr Marco Sonzogni is Reader in Translation Studies in the School of Languages and Cultures at Victoria University of Wellington. He is a widely published translation scholar, an award-winning literary translator, and co-editor, with Tim Smith, of a unique new version of Dante’s Inferno with multiple translators.

And the winner is … Kazuo Ishiguro, “who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world”. Salman Rushdie’s congratulations to his “old friend Ish” – whose work Rushdie has been following with admiration since the 1982 publication of Ishiguro’s debut novel, A Pale View of Hills – included a reference to the fact Ishiguro “plays the guitar and writes songs too!” A clever way of moving past last year’s winner (“Roll over, Bob Dylan!”)? Unnecessary perhaps but so be it.

According to the bookmakers, this year’s hot favourite to succeed the Minnesota minstrel was Haruki Murakami. In Tokyo, some of Murakami’s aficionados cheered Ishiguro – there is something Japanese about the winner after all. Among others tipped to win: Kenyan Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Canadian Margaret Atwood, American Philip Roth and Israeli Amos Oz.

As a poet, I always hope a poet wins, and would love to see the prize awarded to South Korean Ko Un or Albanian Ismail Kadare. Their voices and verse reveal the world around with depth of insight and courage of expression, transcending the linguistic and cultural contexts of origin and journeying into spaces and situations we can all be called on to witness.

-As a poet, I always hope a poet wins, and would love to see the prize awarded to South Korean Ko Un or Albanian Ismail Kadare.

As a literary translator, and leaving aside an obvious bias for Italian Claudio Magris, I would love to see Argentinian César Aira or Spaniard Javier Marías become Nobel Laureates. I am particularly fond of authors who are also translators because their ideas and their language gain focus, strength and perspective from coming into contact with other cultural and literary experiences.

The choice of Ishiguro has left me lukewarm. Have I read his books? Yes, a couple. Did I like them? Not particularly. Will I read more of his works now? Not necessarily. And it is unlikely I will watch again the 1993 film adaptation of The Remains of the Day, which won him the Booker Prize in 1989 and entered him into literature’s hall of fame.

I will, however, read his next novel and not without apprehension. Winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, as Irish poet Seamus Heaney put it, is a “mostly benign avalanche” if not an utter catastrophe. Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil, wife of fellow Irishman and Nobel Laureate Samuel Beckett, famously reacted to the news from Stockholm with an emphatic “Quelle catastrophe!”

-Winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, as Irish poet Seamus Heaney put it, is a “mostly benign avalanche” if not an utter catastrophe

Accepting the prize – which few have willingly turned down, like the French Jean-Paul Sartre, or were forced to turn down, like Russian Boris Pasternak – brings with it never-ending attention and requests as well as more expectations and commitments. Moreover, taxing travels across the globe are a particularly hard and unforgiving challenge: constant strain, mental and physical, can wear out the most vivid of imaginations, affecting the quality of their work. I find this double-bind painful and intriguing at the same time.

Whichever name the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy reveals to the world at 1pm on the first Thursday in October, a chain reaction of agreements and disagreements quickly ripples its way across countries and canons until the following year’s announcement. Interestingly, no other Nobel Prize seems to generate, at least in the public domain, the same level of attention and discussion. Whether we know a great deal, something or nothing at all about physics, chemistry or medicine, we tend to trust the judgement of those tasked with choosing the winner. And aware or not that we may be of individuals, groups and agencies who – often without recognition and sometimes putting their own life at risk – are instrumental in creating a more peaceful and equal world, we tend to quickly forget those who win the Nobel Peace Prize unless social or political controversy keeps their name in the news.

But we are very quick out of the blocks as committed readers and knowledgeable critics, feeling entitled to doubt the literary decision a small committee has been making since 1901. Like in sport, where we all become better coaches, commentators and even competitors, in literature we appoint ourselves as experts. After all, the customer is always right: we get hold of or download books, for ourselves or others, so we must know, even if we have never written one ourselves.

One thing, however, is likely to bring many together in agreement this time round: Ishiguro is nowhere as controversial a choice as Dylan was last year. To some, as has already been noted, this is a safe, even reassuring, decision, if not an outright correction some others feared or hoped for. Almost certainly, Ishiguro will travel to Stockholm to attend the award ceremony in early December and receive the Nobel medal and diploma from the hands of Carl XVI Gustaf, King of Sweden. And the Nobel Lecture is always something to look forward to, as it (more often than not) offers a first-hand and sometimes intimate account of the person as well as of the writer standing at the podium.

-Ishiguro is nowhere as controversial a choice as Dylan was last year. To some, as has already been noted, this is a safe, even reassuring, decision, if not an outright correction some others feared or hoped for

Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki, Japan, in 1954 – nearly a decade since the United States dropped the nuclear bomb on the city in the final stages of World War II – and moved to the United Kingdom with his family when he was five, because his father, a physical oceanographer, accepted an invitation to continue his research at the National Institute of Oceanography. When Ishiguro returned to Japan for the first time, he was already an adult. One should not be surprised, therefore, by his open admission (in an interview with Japanese novelist and Nobel Laureate Kenzaburō Ōe) to being and feeling “distant from Japan”. Indeed, his country of birth features only as an imaginary setting, namely in his first two novels: A Pale View of Hills, his MA thesis in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia, and An Artist of the Floating World, published in 1986.

At the Nobel announcement, Sara Danius, the Swedish Academy’s Permanent Secretary, colourfully described Ishiguro as “a mix of Jane Austen and Franz Kafka” with “a little bit of Marcel Proust”. Former UK Poet Laureate Andrew Motion has offered a more precise and poignant response, noting how “Ishiguro’s imaginative world has the great virtue and value of being simultaneously highly individual and deeply familiar – a world of puzzlement, isolation, watchfulness, threat and wonder.”

This description captures the essence of a writer who has distinguished himself with independent thinking, refrained expression (perceived by some as emotionless aloofness) and the ability to take risks without compromising intellectual and artistic integrity. Indeed, Ishiguro’s most recent works include a fantasy novel, The Buried Giant (2015), and a science fiction novel, Never Let Me Go (2005), which has been variously defined as quasi-science-fiction, pop genre sci-fi thriller, dystopian novel, coming of age novel, and a parable about mortality. Shortlisted for the 2005 Man Booker Prize and included in Time’s 100 greatest English language novels published since the magazine was established in 1923, Never Let Me Go has inspired three sibling works: a 2010 film adaptation in the UK, and a 2014 stage adaptation and 2016 television drama in Japan.

Interviewed by the BBC after the announcement, Ishiguro described the Nobel as “a magnificent honour”, especially because it places him “in the footsteps of the greatest authors that have lived”. These include other Nobel Laureates who have written speculative fiction: the Doris Lessing of the Canopus in Argos series (1979–83), the Nadine Gordimer of July’s People (1981), the José Saramago of Ensaio sobre a cegueira (Blindness, 1995). And maybe Ishiguro’s Nobel nomination came from another writer. Indeed, Nobel Laureates can nominate fellow authors for this highest of literary honours. For example, TS Eliot – who had tallied seven nominations (most of them directly from Sweden) between 1945 and 1948, when he was awarded the prize – nominated Eugenio Montale in 1955, 20 years before the Italian poet would become a Laureate, and in 1956 another Italian poet, Giuseppe Ungaretti, who was never awarded the prize. It is fascinating to see who nominated whom, who made it and who did not.

The website of the Nobel Foundation states that “nominations to the Nobel Prize in Literature can be made by qualified persons only” and “the names of the nominees and other information about the nominations cannot be revealed until 50 years later”.

It is now possible to search the Foundation’s online archive from 1901 to 1965. Sorting the search simultaneously by country of nominee and nominator, and keying in New Zealand for both categories, it emerges that one of the first nominees and one of the first nominators for the Nobel Prize in Literature were from the Land of the Long White Cloud. In 1905, “English language philologist” Godfrey Sweven, “born 1846”, was nominated by John Brown, “formerly professor of English literature” at Canterbury College. The motivation reads simply: “Limanora, the Island of Progress.”

-It emerges that one of the first nominees and one of the first nominators for the Nobel Prize in Literature were from the Land of the Long White Cloud

According to an entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction published earlier this year, Limanora is a mammoth 711-page hardbound novel, the second instalment of a two-part Limanora sequence published in New York and London by GP Putnam’s Sons as Riallaro: The Archipelago of Exiles (1901) and Limanora: The Island of Progress (1903). The books follow the trials and tribulations of “an ethereal man with artificial wings” who is shot down in the South Pacific but “survives to recount his long Fantastic Voyage through a mist-enshrouded Archipelago”. And “several of the described worlds”, we read, are “deeply Dystopian”.

The library at Victoria University of Wellington has two copies of Limanora, hardly ever borrowed: the first edition and the second edition, reprinted by Oxford University Press. More recent editions can be found on Amazon, but they are rather expensive. A digital copy of the book can be downloaded for free, including via the University of California Digital Library, which digitised the copy gifted to the Library by “Prof Slate” with funding from Microsoft Corporation. A very appropriate end, I guess, for a writer who “anatomizes in extraordinary detail” his vision of “a central utopia” where “medical and technological advances have joined together” and created “a calm, efficient economy” that depends on “a central Power Source with advanced Computers, Communication, Transportation, Weather Control and so forth”. All, of course, “to the benefit of a long-lived healthy population”.

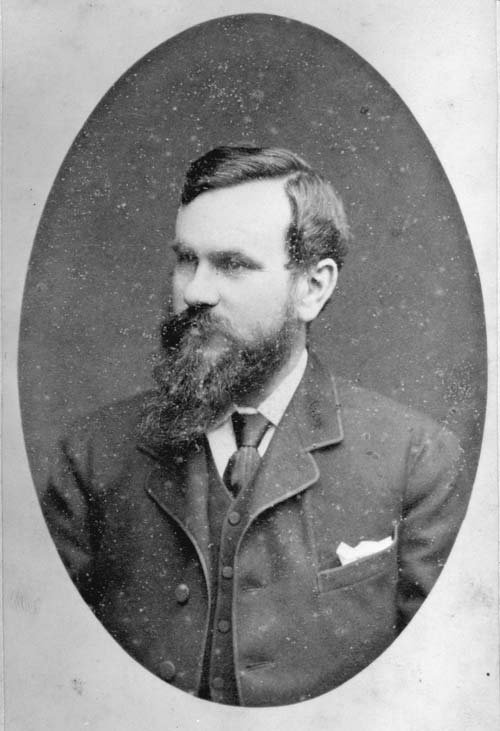

Sweven’s Nobel nomination came from John Macmillan Brown (1845–1935), whose profile in the Nobel Foundation’s archive reads: “university professor and administrator”. This functional one-liner short-sells big time the rich life and work of a remarkable individual who from childhood to adulthood overcame health (severe insomnia), financial (his father’s losses) and personal (the death of his wife and the single parenthood of two daughters) challenges to become an inspiring and innovative (as well as wealthy) academic and administrator. In Cherry Hankin’s detailed entry for the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (1993), we read that Brown was a “natural student”, able to “support himself” and “excelling in both English literature and mathematics”.

Brown’s at-homeness in the humanities and in the sciences enabled him to pursue “wide-ranging interests” and satisfy an “insatiable curiosity about the world around him”. A university position in New Zealand led to his appointment in 1874 as a Professor of Classics and English, “one of three foundation chairs at the newly established Canterbury College in Christchurch”. Regarded as “the outstanding university teacher in New Zealand before 1900”, Brown was a member of the senate of the University of New Zealand from 1877 until his death, and served as its vice-chancellor (1916–23) and chancellor (1923–35). Also, he was one of the first practical promoters in Australasia of higher education for women.

John Macmillan Brown

John Macmillan Brown

With permission from Alexander Turnbull Library

Brown’s “commanding personality” and his concern “to build character and improve moral standards through the study of great literature” made him popular with students and colleagues. His mastery of English literature was “legendary” and his lecture notes “were sold, at first by enterprising students, for distribution throughout New Zealand”.

It is not surprising, therefore, that after his retirement from Canterbury College in 1895 Brown translated his energies into scholarly research and creative writing. What is perhaps surprising is he chose to publish his creative work—two Utopian novels: Riallaro: The Archipelago of Exiles and Limanora: The Island of Progress – under the name of … Godfrey Sweven.

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction entry confirms it, as does a comment at the end of the online entry for Sweven’s nomination on the Nobel Foundation’s website: “Godfrey Sweven has later turned out to be a pseudonym for John Brown.”

When Brown died in Christchurch on 18 January 1935, aged 89, “for several days afterwards the Christchurch newspapers lauded his achievements”. Among them there could have been the Nobel Prize in Literature.

I wonder, in the age of selfies, what to make of Brown’s self-nomination. I am tempted to create a Facebook page in the name of John Macmillan Brown, born in the Ayrshire town of Irvine, Scotland, on 5 May 1845, and grandfather (as a colleague of mine, Peter Whiteford, reminded me) of New Zealand poet James K Baxter … Here is my profile and cover picture. Please like my page!

Dr Marco Sonzogni is Reader in Translation Studies in the School of Languages and Cultures at Victoria University of Wellington. He is a widely published translation scholar, an award-winning literary translator, and co-editor, with Tim Smith, of a unique new version of Dante’s Inferno with multiple translators.